What’s interesting about this speech is that Mrs Fawcett addresses the issue of women protestors arrested at the House of Commons and imprisoned. The Victoria Assembly Rooms were on the east side of Market Square – demolished first to make way for a cinema, and later for a supermarket. Again, I’d love to see photographs of the interior but I fear none survive.

This article is transcribed from the wonderful British Newspaper Archive.

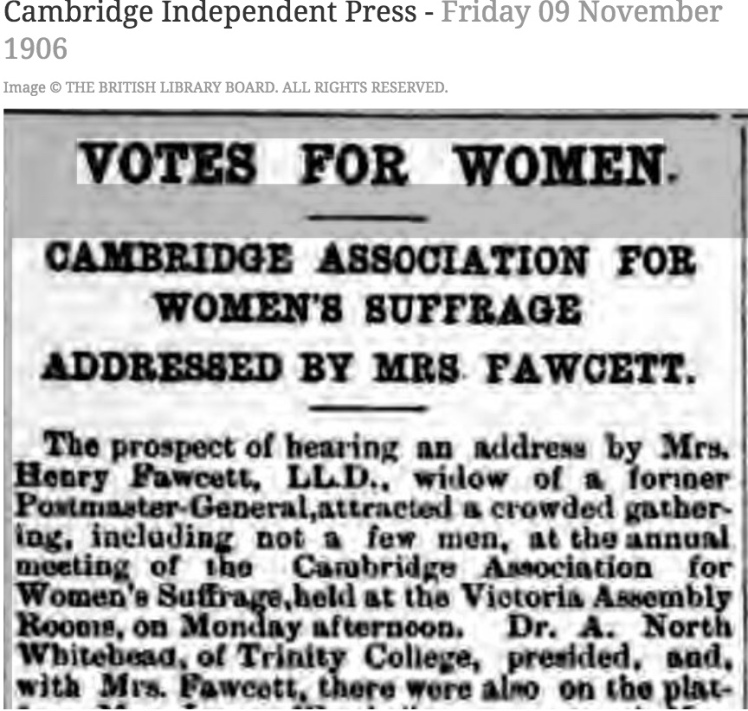

VOTES FOR WOMEN. CAMBRIDGE ASSOCIATION FOR WOMEN’S SUFFRAGE ADDRESSED BY MRS FAWCETT.

The prospect of hearing an address by Mrs Henry Fawcett, LL.D., widow of a former Postmaster-General, attracted a crowded gathering, including not a few men, at the annual meeting of the Cambridge Association for Women’s Suffrage, held at the Victoria Assembly Rooms, on Monday afternoon. Dr. A. North Whitehead, of Trinity College, presided, and, a with Mrs Fawcett. There were also on the platform Mrs James Ward (hon. secretary), Mrs Heitland, Mrs de Bunsen, Mrs Rackham, Miss J. E. Kennedy, and Dr. Westlake (Professor of International Law at Cambridge University).

PROGRESS OF THE MOVEMENT.

“Mrs James Ward presented the report of the Executive Committee, which stated that since the last annual meeting of the Association the cause of Women’s Suffrage both in this country and on the Continent had made great advances, and in Cambridge the forward movement had been particularly marked. The Association had more than doubled its members, and the increase steadily continued. (Applause.) The Committee thought they might safely say that the movement in this country had assumed dimensions and acquired an importance which would make henceforth impossible for Governments either to ignore or despise it, though unless the pressure brought to bear upon them became more solid, systematic and forcible, they might for some time yet delay dealing with the question and evade the Issue.

“The report went on to deal with the deputation to the Premier in May of some 500 delegates from a great variety of societies, with membership of over 300,000, to beseech the Government to extend the franchise to women on the same terms it was now granted to men; the organising by the Committee of the National Union of a vigorous canvass in favour of Women’s Suffrage in the constituencies of Ministers and Members of Parliament opposed to it, and the meetings of the International Women’s Suffrage Alliance in Copenhagen in August, at which Mrs. Fawcett was one of six delegates from Great Britain. A summary was also given of the year’s work of the Association Cambridge, register of women voters, begun some time ago independently by Miss J.E. Kennedy, was completed by the Association.

“In addition to the stirring and entertaining address given by Miss Alice Garland at the last annual meeting, and repeated Newnham and Girton Colleges, addresses were given during the year Mr. H. G. Fordham, Chairman of the Cambridgeshire County Council, the work of local government, at a conference of women householders (voters) in St. Columba’s Hall; by Miss Isabella Ford, of Leeds, dealing with the suffrage from the point of view the women industrial workers, at a meeting of some 200 men and women held by the kind permission of Miss A. M. Smith and Mr. George Smith, J.P., in their garden on Mill-road; and the Secretary to the students of the Women’s Training College.

“The suffrage was also discussed under the auspices of Mrs Rackham at meeting of the Women’s Co-operative Guild, in Burleigh Street; at afternoon “at home” given by Mrs John Chivers, Huntingdon Road, to residents of the neighbourhood; at an afternoon at home” given by Lady Darwin to friends in the Newnham district; and at drawing-room meeting of persons from the Rock Estate district, at the residence of Mrs George Green, Hills-road. It is proposed during the coming year to hold many more similar meetings in drawing-rooms, gardens, or schoolrooms in various quarters of the town, as the opportunity offers.

“The report concluded with an expression of the loss sustained by the Association the death of Sir Richard Jebb [Uncle of Eglantyne Jebb] and Dr. E. S. Shuckburgh. In Sir Richard Jebb, said the Committee, we have lost a supporter of inestimable value. His position in the University, in the political and in the educational world, made his adherence to our cause a most powerful testimony to its reason, its justice, and its practicability. By the death of Dr. E. S. Shuckburgh the Association has lost one of its earliest and best friends and supporters. He was one of the originators of the society in 1881, and he served for many years on the committee. He helped to guide the society through its small and difficult beginnings. For 22 years we have had his sympathy and his influential support. We need not say how much shall miss them.

“The statement of accounts showed that the year was commenced with a credit balance of £22. 10s. 10d. The members’ subscriptions i amounted £l2 7s. 6d., and the total receipts » were £37 15s., the balance in hand at the end of the year being £l3 14s. Id.

TO INCREASE THE MEMBERSHIP.

Mrs Heitland moved an alteration in the first sentence of Rule 2, to read: An annual , subscription (the minimum being threepence) shall constitute membership.” They wanted, she explained, to enroll the women workers and to obtain a greater number of members. She would rather have four persons subscribing threepence, and bringing to the cause their zeal and enthusiasm, than one shilling languidly given. (Applause.) Mrs. Bagstaffe, a working woman, seconded, and it was carried unanimously.

THE ELECTION OF COMMITTEE.

On the motion of Mrs De Bunsen, seconded , by Miss Parry, the following were elected to serve on the Committee for the ensuing year.

- Mrs Adam, (Mother of the founder of modern day social science, Baroness Barbara Wootton)

- Miss Mary Bateson, (Historian, Newnhamite and sister of Mrs Heitland)

- Mrs Dutt, (mother of R Palme Dutt, & who with her husband Dr Upendra Dutt set up the first doctor’s surgery on Mill Road – still there today)

- Miss Flack,

- Miss Frances Hardcastle,

- Mrs Heitland – The Rock behind Cambridge Womens Suffrage Association,

- Miss J. E. Kennedy, (First woman to stand for election in Cambridge – with Rosamund Philpott)

- Miss Paues,

- Mrs Rackham – Clara Rackham, politician and local councillor for half a century in Cambridge.

- Miss Reinherz,

- Mrs J. Ward (Mary Ward Martin),

- and Mrs Whitehead.

DR. WHITEHEAD’S SUPPORT.

“The business having been transacted, the Chairman gave an address, in which he suggested for consideration two points — the effects of the Women’s Suffrage agitation, and the reasons which animated it. As to the effects of the agitation, he said, they had good cause for congratulation. A few years ago the political emancipation of women was merely the dream of a few political idealists; today it was living political issue, popular among large masses of voters. He based his own adherence to the cause upon the old-fashioned formula of liberty; that was, upon the belief that in the life of a rational being it was evil when the circumstances affecting him were beyond his control, and were not amenable his intelligent direction or comprehension.

“Progress in thought, progress in civilisation depended for their good ultimately upon this — that they delivered the life of man into his own hands. But the chief and noblest of the external activities of human beings was concerned with the life of the State, that great organism on whose well-being depended the nature of the opportunities which life could offer to each individual. It followed, therefore, that, except for plain overmastering reasons connected with the necessary efficiency of government, it was a crime against liberty deliberately to deprive any portion of the population of possibilities of political action.

“In the case of women in England at the present time there was no reason for any exceptional treatment which did not also exist for the corresponding class of men. What reasons had been alleged against the enfranchisement of women? It could no longer be maintained that women were prevented by social usage from interfering , politics. Both the great parties in the State now made use of large political organisations of women. At the present time their , influence as a class was necessarily irresponsible _ and often uninformed. When they had the vote they would…

TAKE THEMSELVES SERIOUSLY

“….and form their opinions with a sense of responsibility. Again, they were told that women were virtually represented by the votes of the men. This theory virtual representation was ever the last bad argument of prejudice. In another connection it was long ago examined and torn to shreds by the historian Macaulay. Either the virtual representative will act as his so-called virtual constituents wish — and then, why not give them the direct vote — or the virtual representative will not act as his virtual constituents desire, and then in what sense is he their representative?” Lastly, there was the physical force argument, via, that the ultimate direction of affairs must be vested in those who in their own persons possess the fighting strength of the nation. This argument proved that any despotism was impossible, that any oligarchy was impossible, and when he contemplated those results of the argument he wished it were true. But, unfortunately, it was manifestly false.

“In introducing Mrs Fawcett, Dr. Whitehead said that she bore the name of one whose memory was honoured throughout England as having during a strenuous career exhibited to the full those noble qualities of mind and character which it was the boast of liberty to produce.

MRS FAWCETT AND SUFFRAGE OPPONENTS.

“Mrs Fawcett devoted a considerable portion of her address to criticising arguments put forward by opponents of Women’s Suffrage. One lady opponent based her opposition to it on the ground that the duties of woman lay in the home, and that she could not divide herself between them and politics. They might point out that an exactly similar argument applied to the various occupations of men, which occupied the greater part of their time and attention. If the occupations of the home prevented women from voting, why should not the occupations of banks, finance, agriculture, military affairs, and all those other occupations also prohibit men from exercising a vote? Why should the fact that women knew and cared about the home, and were brought into contact with the various problems incidental to the upbringing of children deprive them of the right of giving a vote, when much of the legislation that passed through the House of Commons had to do with these matters?

“Legislation affecting the home, and that meant the maximum amount of all legislation, would be all the better if looked at and produced by those who knew from practical experience what home duties, the care and education of the young, and the up-bringing of children meant. It was said that if women were given the vote they must never expect to treated with politeness any more. Ladies need not be so much alarmed on that account, because the ladies in Australia said that they had never been treated with so much consideration as since they had obtained the Parliamentary vote — (laughter) — and that consideration became even more marked as the period of election approached. (Renewed laughter.) They also said that they had more power to carry legislation in which women were interested, and that the character of the men chosen candidates was higher than it was before women were granted the vote. (Applause’). It was also asked…

WHY SHOULD WOMEN BOTHER

“…about voting when any lady could get her gardener vote for her? (Laughter.) Mrs Fawcett thought there had never been an argument quite like that since the question was asked: Why should people starve when such excellent buns could be bought for a penny ? (Laughter) The idea that women existed who had not got gardeners or that there existed gardeners who might want to vote for themselves never seemed to have entered into the minds of those who used that argument.

“They might hope yet to see advertisements in the Church papers as follows:

“Wanted, an active young man gardener, to look after the pony and play the organ on Sunday, and vote as required.” (Loud laughter.)

“Primrose League lady, writing from some part of Yorkshire, was opposed to Women’s Suffrage because she had got everything she wanted. I think, continued Mrs Fawcett, there is a great deal too much of the idea of going into politics for something that you want to get. That is not the spirit in which I hope all good women citizens will go into politics. (Applause.) I want women to go into politics for what they can do and what they can give, and not for what they can get. (Applause.)

NO CONSIDERATION FOR WOMEN.

“Mrs Fawcett went on to point out that Professor Westlake and Professor Dicey, of Oxford, had shown without any possibility of doubt that the Trades’ Disputes Bill, if it passed as it now stood, would seriously curtail the liberty which every Englishwoman ought to possess of getting her living in the way which pleased her to do so, and during the debates in the House of Commons not a word had been uttered even to show that such a creature as a working woman existed. If there was a question affecting working men, Members of Parliament ran over one another in their eagerness to show that they were their friends — (laughter) — but no one came forward the friend of the working woman not even those who were their best friends on the question of Women’s Suffrage. They were not asking merely that the weak should be protected. but that the weak should be given the power to protect themselves. (Applause.)

THE IMPRISONED LOBBYISTS

“Before concluding. Mrs Fawcett referred to the women in Holloway Prison, who she thought had been subjected to a considerable amount of misrepresentation and injustice. She gave an account of what happened in the lobby of the House of Commons on the eventful opening day of the Autumn Session, as related by friends who were with the imprisoned women both inside the lobby and outside at the time of their arrest. The women went down in a party to the lobby of the House of Commons and sent in a note to the Prime Minister asking if he would send them message of encouragement about the prospect of legislation on the subject. A secretary came up on behalf of the Prime Minister to say there was no chance whatever of anything being done this Session, or the next Session, or as long tho Liberal Government remained in office.

“Then they became exceedingly irritable. They jumped on the forms and proceeded to make speeches and wave their flags. This was contrary to the rules of decorum which governed the proceedings of strangers in the House of Commons, and they were carried out by the police. (Laughter.) As they were coming out, a young factory worker who had never been inside the House of Commons at all said

“Votes for women.”

She was immediately arrested by the police. Mrs Despard, the sister of General French [Later Commander-in-Chief of the British Expeditionary Force on the outbreak of WWI), who had been making speeches in the lobby, tried to protect the girl. She said to the policeman,

“Why do you arrest this child? Arrest me; I was taking part, and she was not”

The policeman said quite politely,

“We don’t want you, Mrs. Despard, WE WANT KENNEY and Billington.”

“Was that English justice? (“No, no.’’) Was it right to take a young girl, or anybody else for that matter, simply for saying Votes for women the streets No one could say it was. The next day, when the women were taken to the police court, they had their witnesses ready to prove that Annie Kenney was not taking part in the disturbance, but the magistrate absolutely refused to hear any evidence whatever. It was scandalous travesty of Justice, and she hoped very much that an action for false imprisonment would be brought against those who were responsible. (Applause.)

“Some people severely condemned the conduct of those women, but however much they condemned their conduct, they must remember that they had committed no moral crime. She thought that two months’ imprisonment for having behaved in an indecorous manner in the lobby of the House was very excessive punishment — (hear, hear) — and appeared to her indicative of petty vindictiveness. She was quite aware that by saying one word the women could come out of prison, but that was just the thing that had struck the imagination of almost the whole of the English people that they would not say that one word. They felt that if they said that word they would be giving their case away. By refusing to do that, and suffering the hardships and discomforts of prison life, they had killed for ever that old taunt that women did not care for Women’s Suffrage. (Applause.)

RESOLUTION TO THE PRIME MINISTER AND THE BOROUGH MEMBER.

“Miss J. E. Kennedy moved the resolution:

“That this meeting of the inhabitants of Cambridge, members of the Women’s Suffrage Society, and others, believing with the Prime Minister that the arguments in favour of the enfranchisement of women are conclusive and unanswerable, calls upon the House of Commons to fulfil without delay the pledges given by a large majority of the members during the General Election on this subject, and also asks Mr. Buckmaster, the Member for the Borough, [Stanley Buckmaster KC MP, Cambridge 1906-10, later Solicitor General then Lord Chancellor] to promote by every means in his power the introduction and carrying a Bill to confer the Parliamentary franchise upon the same terms those on which it is possessed by men.”

“She felt that the Prime Minister was a sincere friend of the cause, and that if it depended on him alone they would not have to wait long. (Hear, hear.) They knew also that they had a good friend in their Borough Member — {applause) — and that they would not appeal in vain to him to do anything he could help them. (Applause.)

“Professor Westlake, in seconding, said the time had completely gone by when any considerable number of men still thought that it was a matter of principle to keep the government of the country in the hands of men.

“We were on the eve of the reforming of our great Parliamentary institutions, and if Women’s Suffrage was not included in that Parliamentary reform great wrong would have been done.” (Applause.)

The resolution was carried unanimously, and an enthusiastic meeting terminated with a vote of thanks to Mrs Fawcett, proposed Mrs Rackham and seconded by Mrs Bateson, and a similar compliment to the Chairman.